Six iconic designs by Marco Zanuso

Lyrical Rationalism

-

Metal Lambda Chairs by Marco Zanuso & Richard Sapper, Italy, 1959

Photo © FUNDAMENTE

-

Mid-Century Italian Senior Chair by M. Zanuso, 1950

Photo © Castiglia Gallery

-

Mod. TS502 Radio by Richard Sapper for Brionvega

Photo © SAVOY900

-

Regent Sofa in Leather by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s

Photo © Tempi Moderni Design

-

Floor Lamp by Marco Zanuso, 1964

Photo © MF artedesign

-

Mid-Century Baby Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s

Photo © The Dutch Villa

-

Regent Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s

Photo © Solonovecento srls

-

Coffee Table by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, 1970s

Photo © Ventidue snc

-

Woodline Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s

Photo © Conni Kern

-

Square Armchairs by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s

Photo © Maison Rapin

-

Square Sofa by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s

Photo © Maison Rapin

-

Leather Maggiolina Lounge Chairs & Footstools attributed to Marco Zanuso for Zanotta

Photo © ReHaus Furniture Ltd

Between the 1940s and 1970s—the heyday of midcentury modernism—Italian master Marco Zanuso (1916—2001) innovated an array of materials and techniques that had a seismic impact on design history, including the first application of foam rubber in upholstery and the first chair to be entirely fabricated in injection-molded plastic. Many of Zanuso’s greatest achievements involve the nuts and bolts of how the design profession is practiced. But beyond the wonkish details of optimizing industrial processes, it’s easy to see that Zanuso possessed an uncanny flair for form. In piece after piece, he hit that sweet spot between rationalism and sensuality.

To re-up your design nerd credentials, here are six designs that earned Zanuso his paramount place in the pantheon of Italian design:

Lounge Chair for MoMA’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture (1948)

One of Zanuso’s earliest projects—the one that put him on the international stage for the first time—was his entry into the Museum of Modern Art's International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture in 1948. It featured a mechanical joining system of his own invention in which a slim and sinewy tubular steel frame supports a suspended fabric seating “cone,” accompanied by a built-in reading light and drink holder. Although he lost out to the likes of Charles Eames and Robin Day, Zanuso’s imaginative biomorphic lounge chair foreshadows his life-long drive to forge new ground in construction techniques and material use.

Lady Armchair for Arflex (1951)

As a result of the acclaim Zanuso received from the MoMA exhibition, the Pirelli tire company approached him to explore innovative applications for their newly developed foam rubber material. The first idea was to use it in automobile seating, but Zanuso began to envision its use in domestic furniture. “Numerous experiments made it apparent that the implications for the field of upholstered furniture were enormous,” Zanuso later wrote in his 1983 essay “Design and Society.” “It would revolutionize not only padding systems but also structural, manufacturing, and formal possibilities. As prototypes began to take exciting new formal definitions, a company was established to put these models, such as the Lady Armchair, into production on an industrial scale never before imagined.” The company that Zanuso helped to launch was Arflex, one of the first in Italy dedicated to making furniture on an industrial scale. His timelessly charming, oh so curvy Lady Armchair won the Compasso d’Oro prize at the 1951 Triennale di Milano and remains popular today—both the new ones still in production and the vintage classics from last century.

Lambda Chair for Gavina (1959-1964)

Despite his insistence on retaining a great deal of control over his projects from beginning to end, Zanuso did not shy away from collaboration. Most famously, in 1957, he began a two-decade-long partnership with German designer Richard Sapper, with whom he shares credit for some of the most iconic works of 20th-century Italian industrial design. One such icon is the deceptively simple, sturdy yet elegant Lambda Chair. Before the final product went into production with Gavina

around 1964, Zanuso and Sapper had for years explored a variety materials before settling on a hyper streamlined fabrication process borrowed from the auto industry, in which sheet metal is stamped out, spot-welded, and spray enameled. The Lambda proved that high-tech could be highly desirable in the domestic realm, and the research behind it led to another Zanuso and Sapper icon: the Model K4999 Child's Chair.

K4999 Child's Chair for Kartell (1960-64)

Zanuso’s most internationally successful design, the K4999 for Kartell, also turns out to be the one that most exemplifies his holistic, research-driven approach. His recount of the intensive path that led from the Lambda to the K4999 in “Design and Society” makes plain just how meticulous he could be: “The formal and structural implications of this concept… required more than 50 prototypes to develop it to the point of industrial production… But even at this point, research in our office continued. In connection with a commission to design classroom furniture for the city of Milan, we had already been experimenting with a scaled-down stacking version of the Lambda for elementary schools. As we were looking for alternatives to sheet metal, a material inappropriate for this particular application, a notable drop in the price of polyethylene on the expiration of international patents opened up completely new possibilities. This new material, in turn, led to a rethinking of the formal and structural characteristics of the chair and, consequently, to much additional research. The final result, the Child's Chair, surprised even us; because of the various stacking possibilities we had developed as a result of structural requirements imposed by the use of polyethylene, we had created a chair that was also a toy, which would stimulate a child's fantasy in his construction of castles, towers, trains, and slides. At the same time, it was indestructible, and soft enough that it could not harm anyone, yet too heavy to be thrown.” It represented the very first structural application of polyethylene plastic in furniture.

Grillo Folding Telephone for Siemens (1966)

A symbol of postwar Italian modernity, the Grillo Telephone designed by Zanuso and Sapper for Siemens gets its name from the “cricket” sound it makes when it rings. But the delightful biomorphism of this design does not end there. When it’s not in use, it folds up like an animal retracting into its compact protective shell. The interactive parts—dial, speaker, and microphone—are revealed only when it’s opened. Earlier phone designs separated the handset and cradle into two pieces, but the Grillo contains everything in a single body, with a long tail of cord coming out one end for greater portablility. Though less known outside of Italy, Zanuso’s and Sapper’s Grillo came to be seen by phone designers (we’re looking at you Jony Ives) as an influential design step toward mobile phones.

Mobile Housing Unit, Prototype for MoMA’s Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (1972)

Long before everyone was raving about "Tiny Houses" and "Micro Homes," Zanuso and Sapper collaborated on their precient and well considered Habitation Units, which debuted at the landmark New Domestic Landscape exhibiton at MoMa in 1972. With a shipping container as its starting point, this design was an experiment in “complete and fully equipped habitation, easily transportable, and ready for immediate use,” aimed especially at temporary, large-scale public works communities, areas that have suffered catastrophe, and other destinations set in fragile natural surroundings. Though the project never went further than the prototyping phase, its influence is clear. The images that have survived from the 1972 exhibition look as fresh as anything found this year on the pages of Dwell and Wallpaper*.

This story has been excerpted and edited from an essay in Kinder Journal, published by the child design experts at Kinder Modern in New York. Head over to Kinder Journal for fascinating and charming stories about child-centered design—past, present, and future.

-

Text by

-

Wava Carpenter

After studying Design History, Wava has worn many hats in support of design culture: teaching design studies, curating exhibitions, overseeing commissions, organizing talks, writing articles—all of which informs her work now as Pamono’s Editor-in-Chief.

-

More to Love

Italian Cotton & Velvet Lady Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s

Italian Martingala Chair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s

2-Seat Triennale Sofa by Marco Zanuso for Artflex, Italy, 1951

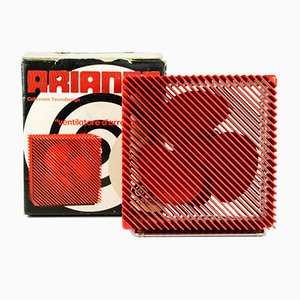

Ariante Fan by Marco Zanuso for Collezioni Techno Design, 1970s

Woodline Lounge Chair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, Italy, 1964

Ts 505 Portable Cube Radio by Richard Sapper & Maro Zanuso for Brionvega, Italy, 1970s

Vintage Reclining Lady Chair in Wool by Marco Zanuso for Pizzetti, 1960s

Modern Woodline Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1970s

Senior Armchairs by Marzo Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s, Set of 2

Triennale Model Sofas by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s, Set of 2

Woodline Armchairs by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s, Set of 2

Armchair Lady by Marco Zanuso for Arflex,1951

Italian Senior Lounge Chairs by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, Set of 2

Square Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Techniform, 1960s

722 Woodline Armchairs by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960, Set of 2

Vintage Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s

Square Armchairs by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1960s, Set of 2

Coffee Table by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, 1970s

Armchairs, Sofa and Coffee Table by Marco Zanuso for Poltronova, 1960s, Set of 4

Lady Armchair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, 1950s

TS 505a Radio by Richard Sapper for Brionvega

Italian Lady Lounge Chair by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, Italy, 1950s

Wood and Glass LB65 Cabinet or Bookcase by Marco Zanuso for Poggi, 1968

Celestina Folding Chair in White Leather by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta

Sideboard in Black Lacquer by Marco Zanuso for Elam, 1970s

Coffee Table by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, 1970s

Mid-Century Early Edition Lady Chair with Wooden Frame by Arflex, 1950s

Italian Table in Crystal and Steel by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, 1960s

Mid-Century Italian Armchairs with Check Fabric by Marco Zanuso, 1950s, Set of 2

Vintage Maggiolina Lounge Chair and Ottoman by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, Set of 2

Square Glass and Chrome Coffee Table by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, Italy, 1960s

Table by Marco Zanuso for Zanotta, Italy, 1960s

Lambda Zanuso & Richard Sapper for Gavina, 1950s

Photo © Neef Louis Design

Lambda Zanuso & Richard Sapper for Gavina, 1950s

Photo © Neef Louis Design