A studio visit with London ceramicist Tessa Eastman

On the Cutting Edge of Tradition

Not long after I encountered the work of ceramicist Tessa Eastman, I shared pictures of her exquisite, alien-like ceramics with a designer friend. “What, she’s into 3-D printing?” he asked, questioning my enthusiasm. “No,” I said. “She makes them by hand.” He grabbed my phone and began to zoom in.

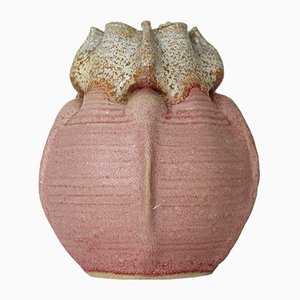

Born and based in London, Eastman is an innovator in a traditional field, possessing a demeanor that’s both humble and well studied—heartfelt and cerebral—just like her work. But whereas Eastman herself demures from the spotlight, her vibrantly hued, multidimensional ceramic sculptures and vessels leap out from the background and grab your attention right away. For ceramics enthusiasts, Eastman is a marvel because her techniques require deep knowledge of age-old clay manipulation, as well as the latest science behind the production of pigments and glazes. “How does she do it?” is always the first question. Followed by, “And how does she achieve those colors and textures?” Yet even those who know little about the contemporary craft scene find Eastman’s work to be unforgettable. It’s just so unique.

We had the pleasure to meet Eastman in her studio to see firsthand where the alchemy happens. Read on to get know one of contemporary ceramics’ rising talents.

WC: A portion of Pamono’s audience may be new to ceramics. Can you tell us what, for you, makes this material so special?

TE: Ceramics as a material is magical. With skill, it can be manipulated; with science, it can be transformed from pliable mud to a fixed, permanent form. The fact that the material is the very essence of the earth—coming from the ground beneath us and with a history as ancient as human civilization—gives it a unique vitality. For me, this energy is increased when it is used by makers today to explore contemporary aesthetics. The interplay between this ancient material and fresh ideas excites me. I try to push the material to its sculptural limit in order to produce objects filled with expression and sensitivity.

To appreciate ceramics, one must look to understand the physicality of the material and the distinctive quality of handcrafted objects. The market for ceramics may be quite small compared to mass-produced consumer products, but it’s definitely expanding. I think people are starting to see that beautiful, decorative items for the home are as “necessary” as anything else. Everyday life is so much richer when it’s full of unique, handmade objects in which the soul of the maker shines through.

WC: You’ve studied ceramics in a variety of impressive institutions since you were a teenager. Can you share how your work has evolved through the years?

TE: I feel extremely privileged to have had the opportunity to study at the Wimbledon College of Art, the University of Westminster, and the Royal College of Art. The tutors I encountered at these institutions have shaped my work in significant ways.

I was greatly inspired by my tutor and well-respected ceramist Annie Turner at Wimbledon College. Annie’s work is closely linked to the River Deben in Suffolk and her family’s connections to this area. We both share an affinity for surface as well as the earth’s seasonal rhythms that mark the progress of time. Annie taught me that less is more—which I initially found difficult to grasp, since I have an innate affection for maximalism and intense color. I produced an installation of sculptures based on bones, shells, seaweed, and beach-found objects that rested on and within imprinted rock, footprints, and sand tiles. I used an array of textured glazes that were based on sea and sand colors.

At the University of Westminster (often called Harrow, because it grew from Harrow Art College), I was lucky to have tutors who are also practicing sculptural ceramic artists. Steve Buck had a big impact on my work, since we both share a love of time-consuming, complex hand building with the occasional use of mold making. He encouraged me to embrace the peculiar and macabre, and I produced work following this style for eight years. I constructed the popular Burning Slices of Death Cake, which was shown at Five Decades of Harrow Ceramics in 2012 at London’s Contemporary Applied Arts, and Melon Berry Burst, which depicts a large sprouting flower with legs acting as stamens—it looks like humans were being swallowed up. This sold to an eccentric ceramic collector at the degree show.

After some time, I was yearning for something new within my work; hence my decision to apply to the Royal College of Art, where I studied from 2013 to 2015. Renowned ceramist Felicity Aylieff taught me to think in an entirely new way there, abandoning naive kitsch and delving much deeper into the curious ambiguity found in natural phenomena and microscopic organisms. Excellence in construction was paramount, and I was encouraged to be brave and experimental. I developed my own range of high-firing glazes that have unusual depth and texture (unlike the bright, flat commercial glazes that I used at Harrow). I produced Residing Cloud and Blood Crystal in Midnight Element, which sold at the degree show.

WC: At our first meeting, we discussed that ceramics seem to be having “a moment.” Why do you think this is? Do you see it within any broader cultural trends?

TE: Life today, especially in cities, is moving at a faster pace than ever before. Many people work in desk jobs, and there is an increasing demand for a more holistic way of living—hence the organic food craze and the fashion for yoga and Pilates. I am witnessing a rising number of students enrolling in pottery courses, where people are motivated by a desire to use their hands, get messy, and find a sense of balance within their busy lives. TV shows, like the BBC’s The Great Pottery Throw Down, have raised much awareness about pottery too.

It’s great to see big furnishing stores such as Heals promoting handmade, ethically sourced craft by contemporary makers, rather than mass-produced wares from abroad. They have brought makers into the store to demonstrate their skills to the public. I see more top restaurants using artists’ or designers’ works, rather than standard mass-produced ware. For example, Sketch had a range by David Shrigley, and if one goes to one of their tearooms, all the china is vintage and un-matching, which provides for a unique experience.

People are ever more searching for beauty and new experiences. I feel ceramic sculpture enriches lives by encouraging contemplation and reflection. Ceramics especially brings us back to our human roots and reminds us of the important fundamentals in life—space, balance, and joy.

WC: You’ve mentioned that you’re attracted to the “strangeness” of the world—or at least attracted to engaging the strangeness of the world. How does your work seek to do this? How do you hope people will respond?

TE: I have always been inspired by the strange otherworldliness that I see in everyday life. My early work took on a kitsch aesthetic, and I adapted innocent children's toys, transforming them into humorous, macabre ceramic sculptures. Today, I observe the strange systems and abnormalities seen in natural phenomenon and compare this to human relations. To me, human sentiments mimic the ever-changing cycles found in the earth’s patterns. Nature and humans follow an order, from birth to decay. And yet during this period, things can tilt off balance or run off course, as change is inevitable.

I connect with fleeting clouds in my work, for example, and enjoy the dichotomy that they can be both dreamy and full of possibility while also leaving the imprint of impending doom. I relish this outlandish contrast along with the ever-changing formation of clouds. The idea of contrast or clash is where I find peace, as opposites attract and create equilibrium. There is optimism when two variances combine; if life were only upbeat, there would be no sense of appreciation. Downcast moments help one to appreciate pleasure and connection.

It is my intention that people will connect with the idea of their own impermanence in some way and appreciate the moment they are in now. I hope people will appreciate a less classical aesthetic of beauty and that this in turn will help them appreciate the messy business of life that we all take part in. Having others find their own connection is most important to me. It’s one of the great joys I receive from being a maker.

WC: How do you think about the historical distinction between design and craft in your own work?

TE: As people seek new ways of making, new materials and new opportunities, disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred. For example, traditionally trained craft makers now use 3-D printing techniques to make pots, which ironically mimics the most ancient way of making pots. Using coils of clay is how the 3-D printer works, coiling up shapes electronically via a computer design.

Whilst at the Royal College, product designers and architects would try to scheme their way into the ceramics department to use the facilities, which would cause concern with technicians as equipment is highly specialized and is not suitable for beginners. Someone working in design approached me recently to ask if I would teach him how to throw. Little did he realize it is not a skill to be mastered in a few days, but in years with dedicated practice!

But I do think about the differences in my own work. It seems it is not enough today to make work for only one arena. A lot is about branding and getting the work in the right places for the right people to take notice. It is up to the ceramicist, designer, architect, and fine artist to choose where he or she would like to be positioned in the marketplace, depending on the style of work.

My work leaves the studio to go to interior design outlets, contemporary ceramic galleries, and fine art galleries where it’s presented alongside painting and sculpture. I have shown in places that specialize in vintage and antique furniture, such as Biedermeier and Art Deco, and the pieces really complemented one another. I have recently been asked to produce a functional collection to go into Michelin star restaurants, which will need consideration, as my glazes are not intended for food.

The good aspect of this contemporary scene is that we have high demand for high quality, handmade contemporary expressions. I have tremendous opportunities to continue perfecting my skills, my craft. I strive for my work—no matter what form it takes—to have a timeless feel. In that sense, I have to admit there is an air of the traditionalist in me.

* If you have the chance, check out Eastman’s work in person, exhibited alongside new work from Michal Fargo, at Brussel’s Puls Contemporary Ceramics Gallery, 11 March to 15 April, 2017.

-

Text by

-

Wava Carpenter

After studying Design History, Wava has worn many hats in support of design culture: teaching design studies, curating exhibitions, overseeing commissions, organizing talks, writing articles—all of which informs her work now as Pamono’s Editor-in-Chief.

-

-

Photos by

-

Marco Lehmbeck

Born and raised between forests and lakes near Berlin, Marco studied creative writing in Hildesheim and photography in Berlin. He’s also part of the organizational team behind Immergut indie music festival. He loves backpacking, Club-Mate, and avocados, and he always wears a hat.

-

More to Love

Futuristic Punk Red-Sea Creature Morphology F by Gilli Kuchik & Ran Amitai, 2016

Futuristic Punk Red-Sea Creatures, Morphology C, #1 by Gilli Kuchik & Ran Amitai, 2016

Pink Pot by Kirstin Opem

Tall Stoneware Pot by Kirstin Opem

Fimo Vase by Gilli Kuchik & Ran Amitai